12/2018 – 07/2019

This is a project that was supposed to be a trip report. In November 2018 I had made plans to take 4TF on a trip out to visit Evan in San Francisco, with a stop to see a high school friend in Las Vegas. I never made it to Las Vegas.

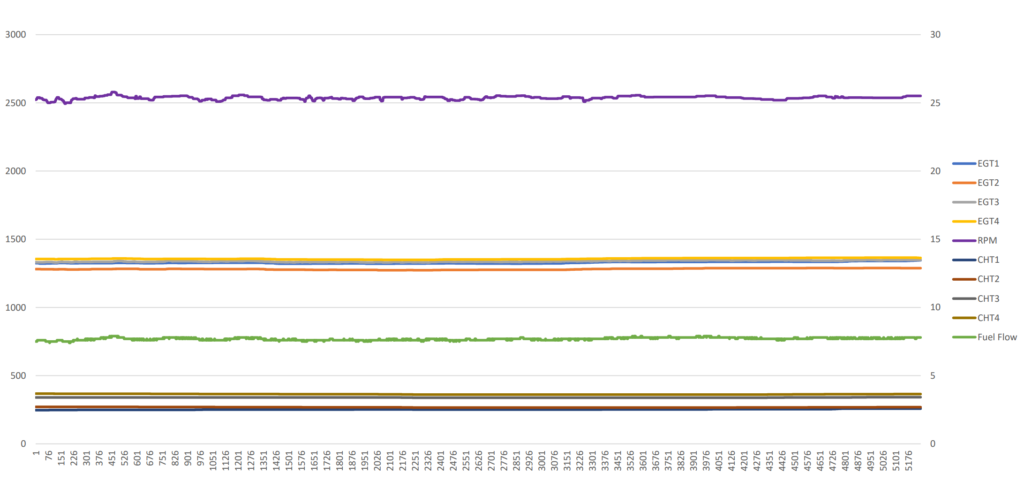

For over 7 years and 450 hours of flight time, the following chart depicts the way my angle valve Lycoming performed. Flawlessly. It always ran smooth, having pushed my Cozy to all three coasts, and dozens of other long cross country flights. It never failed to get me home, and never gave me any reason to worry about it’s health. What you see below is the last 15 minutes before trouble started.

And then the trouble started. At position (A) the engine began to misfire slightly, and I noticed the fuel flow had dropped slightly as had the EGTs. As I increased the mixture, EGT on Cylinder 2, 3, and 4 returned to normal, but Cylinder 1 only leveled it’s decline. The misfire continued, and at position (B) I attempted to increase mixture again, but the misfire continued. I decided to try running on one ignition system at a time to see if I could isolate the issue to one of the ignition systems, so at position (C) I richened the mixture drastically and switched ignition systems off one at a time (hence the RPM drop in the log). This had no effect, and I tried one last time to lean the mixture out hoping it was just a fouled plug. At position (D) the EGT on Cylinder 1 continued to drop and the misfires were getting more prevalent. It was at this point I decided the trouble must be mechanical in nature, and I should land immediately.

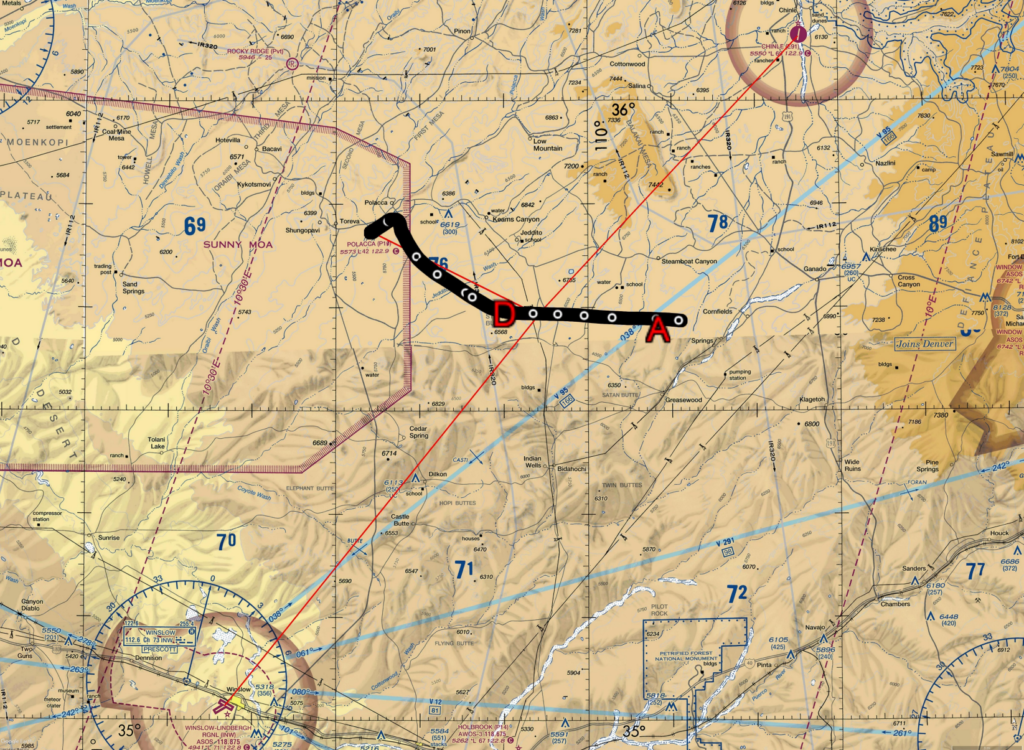

The map below shows the flight path during this particular 15 minute segment. Position (A), marked at the beginning corresponds with the point at which I first noticed the misfire issue and began to troubleshoot. Position (D), approximately 6 minutes later, indicates the point at which I decided the issue was not correctable in flight, and I needed to land immediately. Hitting the nearest button on the EFIS brought up Polacca (P10) 18NM to the WNW, Chilne (E91) 36NM to the NE, Winslow (INW) 48NM to the SSW, and Window Rock (RQE) 51NM to the E. Winslow would have had the most services of all the options, but at that moment my biggest concern was for the safe termination of the flight, not for the ease of repair efforts. Polacca being the closest, indicated a 4200 foot, hard surface runway. That was plenty of length to get me down, so I quickly turned the plane for Polacca. The engine continued to run rough throughout the entire approach and landing, getting worse and worse until I reduced the throttle entering the downwind leg. At that point it actually ran a bit smoother throughout the remainder of the approach and landing. Nearing touchdown I could see the runway was in poor condition with lots of cracks and weeds, but aside from being bumpy, it served me well to get the airplane safely on ground.

Once the plane was safely shutdown, I pulled the engine cowls to see what could possibly be the problem. It didn’t take long to find.

Of the 8 cylinder base nuts that hold the #1 cylinder to the crankcase, 6 were missing. The studs all snapped off. The only two remaining were the crankcase through studs. After complete disassembly and inspection, the prevailing theory is that the stud shown under marker A was the first one to snap. You can see that this particular stud has an asymmetric, twisted fracture line, with corrosion evident around the edge. This seems to suggest that the stud was over torqued at some point in it’s life, thus fracturing the stud and allowing corrosion to begin. The other studs all were snapped cleanly in the valley of the threads, which is the natural stress riser created during manufacturing. Once the first stud snapped, the increased vibration and loads on the other studs reduced the number of cycles before they failed due to fatigue. I can’t say for certain when the first stud snapped, it’s usually hidden from view by cylinder baffling. The last time the cylinder hold down nuts were inspected was during condition inspection 10 months prior. It’s possible it snapped at any point after that.

Obviously there was no field repair to be made here, the airplane would need to be disassembled and trailered home. Upon hearing my troubles, my good friend Bob offered to help me get with what was eventually dubbed project “Wayward Tango Foxtrot”. I took a commercial flight back to Saint Cloud, while Bob loaded up his Cozy to fly from Waukesha to Saint Cloud. I gathered up a number of tools and rented a 4 place snowmobile trailer from a rental depot in Minneapolis. The next morning Bob and I departed for the 26 hour drive from Saint Cloud to Polacca.

Once in Polacca, we spent the next few days getting the wings and canard removed and securing everything on the trailer. Once loaded, we still had the onerous task of pulling it over 1500 miles across country safely. The first issue we would realize as we set off for home was that while my SUV had sufficient towing capacity for pulling the 1200lb Cozy on a 1000lb trailer, the drag from the way the plane was loaded would take it’s fuel efficiency from the usual 28-29 mpg, to a mere 9 mpg. We knew it would drop, but that was definitely more of a drop than expected. This meant we were going to need a lot more fuel stops, and this more over the road time. Neither Bob nor I felt it was wise to drive this load at night, as we were right at the max width limits, and night would make it even more difficult to spot obstacles. The next issue we found was that north Texas in the winter can have major ice storms. Four inches of ice created treacherous roads and road closures, further delaying our travel. It took us three days to get the Cozy safely back to Saint Cloud. But it arrived without so much as a scratch on it for all it had been through. I, on the other hand, had severely bruised emotionally by the event. If it hadn’t been for Bob’s unselfish assistance and words of encouragement along with the overwhelming hospitality of the people of Polacca, I would likely have left 4TF behind for good.

Now back at Saint Cloud, it was time to set about the task of rebuilding; figuring out what went wrong and attempting to ensure it didn’t happen again. Step one was to remove the engine, tear the engine down, and see how bad the damage was beyond the obvious issues of the #1 cylinder hold down studs. I took the disassembled engine back to Bolduc Aviation in Anoka, who had conducted the bulk of the engine rebuild that was done before installing it on 4TF initially. The prognosis was better than I could have hoped. There was no damage to the crankcase, crankshaft, connecting rods, or cylinder assemblies. Reconditioning would be possible. The only bad news was that the shop was pretty backlogged. It was going to take time. In truth this was not the worst thing in the world, as I would need some time to reassemble the rest of the airframe, and I wanted to refinish the engine mount as well.

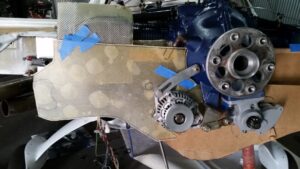

Bolduc completed the reconditioning of the crankcase, crankshaft, connecting rods and cylinder assemblies in April, and set about the task of reassembling the engine with the assistance, once again, of my EAA tech counselor Tim. After remounting the engine I wanted to replace all of the aluminum baffles with fiberglass ones so that I wouldn’t have to ever worry about cracks in them. It would also afford me the opportunity to make them fit better, and most importantly, NOT hide the cylinder hold down studs so that I could inspect them EVERY time the cowl was off. This took a bit of work, but the end result was a wonderful set of baffles that fit perfectly against the engine and the cowl.

After the initial rebuild almost 10 years earlier, I had Bolduc break the engine in on a test cell. This was due mostly to the fact the initial flight testing regime is not conducive to the requirements for engine break-in. I had somewhat lost sight of that reason this time around, thinking that I should once again conduct break in on the test cell. Unfortunately, getting that scheduled proved difficult due to the Bolduc’s backlog. I started thinking of all sorts of idea of how to break the engine in on the ground and yet keep it cool. Eventually I called Lycoming for their opinion on how to do this. They asked the one question that reminded me I didn’t need to prove out the airframe again, just the engine. “How’s your cooling in the air?” they asked. “It’s great.” I truthfully replied. To which they asked, “So why not just conduct the break in airborne?” Ugh. How could I be so stupid? Was I just afraid to actually fly it again? All I had to do was stay high over the airport, and follow the service instructions for break in operation. So that’s what I eventually did. Everything went well. The engine ran smooth as silk, and the temps all stayed perfectly fine despite an outside air temp of 85F. From the ashes, 4TF flew again. All thanks to the help of friends, family, and complete strangers on the other side of the country.